|

The Burning Times (containing excerpts from Laurie Cabot's "Power of the Witch"

|

|||

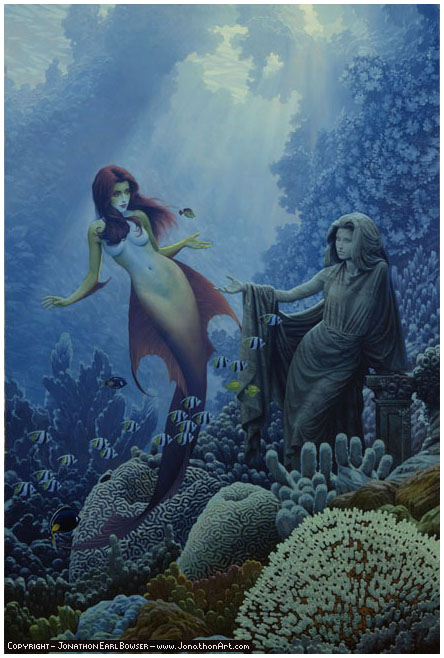

Artist: Jonathon Earl Bowser - Used with permission

|

|||

|

|||

|

The history of Christianity is the history of persecution. Christian forces have consistently harrassed, persecuted, tortured and put to death people whose spirituality differed from their own - Pagans, Jews, Muslims. Even groups within the Christian community itself, such as the Waldensians and Albigensians, suffered under the strong arm of the church (walk through the church door above for more details ....and prepare to be surprised!). Any group or individual whom the ecclesiastical authorities branded a heretic could be tried and executed.

As Christianity spread around the globe indigenous peoples who stood in its way or disagreed with its teachings were accused of devil worship. We find this argument justifying the persecution of native peoples in Europe as well as in the Americas, Africa, Polynesia, the Orient and within the Arctic Circle. Christian armies and clergy, blinded by a patriarchal and monotheistic worldview, have seldom understood the value of spiritual paths different from their own. They have repeatedly failed to see the sacred wisdom in other cultural traditions based on different perceptions of the divine power. In many instances they have not even bothered to look for it. They have shown no compassion, understanding or tolerance for native pantheons.

When Constantine made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, the war against native religions commenced in earnest. Sacred shrines were sacked and looted, springs and wells polluted, priests and priestesses discredited or executed. The first Christian emperor himself embodied the fierce violence that in time would be directed against Witches. He boiled hi wife alive, murdered both his son and his brother-in-law and whipped a nephew to death. During his rule the seeds were sown for the political-military-ecclesiastical establishment that would dominate medieval society. He gave bishops the authority to set aside judgements of the civil courts, and he instructed the courts to enforce all episcopal decrees.

Over the next thousand years patriarchal prejudices against women became institutionalized in the church-state structures of medieval Europe. In the century after Constantine, for example, St Augustine argued that women did not have souls. This abominable theory was eventually debated at the Council at Mācon in the sixth century, and Celtic bishops from Britain argued successfully against it. Thus it did not become official church doctrine. Nevertheless, the idea continued to find supporters among individual churchmen for centuries to come.

Later, St Thomas Aquinas constructed a rationale for treating women like slaves. He wrote, 'Woman is in subjection because of the laws of nature, but a slave only by the laws of circumstance ........ Woman is subject to man because of the weakness of her mind as well as of her body.' This infamous argument was carried further by Gratian, a canon lawyer of the twelfth century: 'Man, but not woman, is made in the image of God. It is plain from this that women should be subject to their husbands, and should be as slaves.' So by the teachings of the church fathers, women fell from being a natural reflection of the Great Goddess and Mother of All Living Things to the lowly position of a slave, not made in the image of God, and possibly not having a soul.

The respected historians Will and Mary Durant have written that 'medieval Christendom was a moral setback' for Western civilization. Many non-Catholic historians have agreed with them. Otto Rank has pointed out perhaps the reason for this moral setback. The history of civlization, he says, was 'the gradual masculinization of human civilization'. Certainly, in its extreme and paranoid style, the male ethos, blinded by its own patriarchal values, has run rampant in its subjection of half the human race and in its desecration of the earth and its resources.

Christendom did not become the dominant faith overnight, and for centuries the Old Religion and Christianity co-existed. In AD 500 the Franks' Salic law made it illegal to burn a person for practising magic, and in 785 the church Synod of Paderborn set the penalty of death for burning a Witch. For a while it appears that not only did the church not fear Witchcraft, it didn't even take it seriously. The Canon Episcopi declared that Witchcraft was a delusion and it was a heresy to believe in it. But by the time of the Reformation attitudes had changed. Both John Calvin and John Knox claimed that to deny Witchcraft was to deny the authority of the Bible, and two centuries later John Wesley stated, 'The giving up of Witchcraft is in effect the giving up of the Bible.' Clearly, Witchcraft was here to stay - Christendom needed it to preserve the integrity of the Bible.

For a long time the Christians, too, practised magic. St Jerome, for example, preached that a sapphire amulet 'procures favour with princes, pacifies enemies and obtains freedom from captivity.' And he didn't mean that it could be used as money to buy these favours! Pope Urban V promoted a cake of wax called the Agnes Dei, or Lamb of God, which protected against harm from lightning, fire and water. The church routinely sold charms to prevent disease and enhance sexual potency. From the seventhto the fifteenth centuries church literature discussed the widespread belief that a priest could cause death by saying the Mass of the Dead against a living person. Presumably, some priests performed this black magic. Until a late date both civil and church authorities used Witches to raise thunderstorms during battle if a good, rousing tempest would help their cause. The church fathers explained this by saying that God allowed the Witches' power to work. Even today remnants of Christian magic can be found around the world in the form of medals, holy water, relics, statues for automobile dashboards, and any blessed object that is used for protection or special favours.

So for a number of years magic seems to have been favourably regarded, even by some people within the church. Witches continued to hold respected positions as healers, nurses, midwives, seers and wise ones versed in the folk customs and beliefs of the people. Throughout Europe there were strong pockets of Old Believers.

But gradually the Christians began to distinguish between sorcery and magic. In 1310, for example, the Council of Treves made conjuring, divination and love potions illegal. These were considered magic. And yet books on sorcery were published under the auspices of the church even with ecclesiastical approval. Von Nettesheism, one author of approved books on sorcery, actually learned his magic from Abbot John Trithemius. What was the difference? The difference was the sex of the practitioner. Men performed sorcery. Women did magic. Sorcery was acceptable, magic was not. In reality, of course, magic is magic. What the church was aiming for was not the elimination of magic or sorcery but the elimination of women practitioners.

Another development in church politics set the stage for the persecution of Witches. It is clear from written correspondence by priests who served in the Inquisition that when the Albigensian and Waldensian heresies had been stamped out in the thirteenth century, church inquisitors worried about their careers. In 1375 a French inquisitor complained that all the rich heretics had been put to death. 'It is a pity,' he wrote, 'that so salutary an institution as ours should be so uncertain of its future.' Witch-hunting was bit business. Nobles, kings, judges, bishops, local priests, courts, townships, magistrates and bureaucratic clerks at all levels, not to mention the actual Witch-hunters, inquisitors, torturers and executioners, profited by the industry. Everyone received a share of the property and riches of the condemned heretics. Should such a 'salutary' institution go out of business? Pope John XXII thought not. He mandated that the Inquisition could prosecute anyone who performed magic. Soon inquisitors were finding magic-workers everywhere. The entire population of Navarre in France was suspected of being Witches!

The word Witch has meant different things to different people in different periods of history. One of its acquired meanings in the late Middle Ages was 'woman', especially any woman who criticized the patriarchal policies of the Christian church. In the fourteenth century, for example, women who belonged to the Reforming Franciscans were burned at the stake for Witchcraft and heresy. Church literature grew increasingly strident in its teaching that women were a threat to the community because they knew magic. Over the years the campaign worked: in the popular mind women who knew the ways of the Craft were considered evil.

The single most influential piece of propaganda in this campaign was commissioned by Pope Innocent VIII in 1484 after he declared Witchcraft to be a heresy. He instructed the Dominican monks Heinrich Kraemer and Jacob Sprenger to publish a manual for Witch-hunters. Two years later the work appeared with the title Malleus malificarum, or 'The Witches' Hammer'. The manual was used for the next two hundred and fifty years in the church's attempt to destroy the Old Religion of Western Europe, demean women healers and spiritual leaders and create divisiveness in local communities in order to strengthen the political and economic factions that the church supported (and that in turn supported the church).

Demeaning Witches demeaned all women, for Kraemer and Sprenger's arguments against Witches grew out of their patriarchal fears about women in general. According to the Malleus malificarum, no woman had a right to her own thoughts: 'When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil.' (This, incidentally, was an argument used at the turn of the present century to deny women the vote - they might think and vote independently of their husbands!) The two monks rehashed Aquinas's argument about women being physically and intellectually inferior to men. 'They are feebler both in mind and body ..... Women are intellectually like children ...... [They] have weaker memories, and it is a natural vice in them not to be disciplined but to follow their own impulses without a sense of what is due.' In short, Kramer and Sprenger's propaganda about woman is summed up in their words that 'she is a liar by nature .... Woman is a wheedling and secret enemy.'

The Christian clergy were not alone in their condemnation of women. The writers of the Talmud wrote, 'Women are naturally inclined to witchcraft' and 'The more women there are, the more witchcraft there will be.'

Could it be that these male writers intuited woman's innate power and correctly saw its relationship to divine power? Woman's power is of the Goddess. Whereas some people have found that notion comforting, patriarchal church leaders found it threatening. In their attempts to monopolize all visionary experience, all the healing arts and all magical practices that enhance human life, they turned the source of life, woman, into an enemy. And they waged war against that 'enemy' so effectively that some European towns were left with only one woman.

In Sprenger and Kraemer's manual Witches were depicted with all the same characteristics that the church had used to describe Jews in the centuries before: they were said to worship the devil; to steal the Eucharist and crucifixes from Catholic churches; to blaspheme and pervert Christian practices; to ride on goats. Kraemer and Sprenger even used the same descriptions for Witches that had been used for Jews: horns, tails, and claws - i.e. the stylized images that artists had devised to depict the Christian devil.

The motives that orchestrated and precipitated participation in the Witch-hunts were a tangled web of fears, suspicions and sadistic fantasies. It's not always easy to discern logic or reason. But we can start with one of the major problems that church leaders faced regarding their conquest of European communities; it was never complete.

Throughout Europe there were people who continued to worship the old Gods in the old ways. The church's frustration over this led it to destroy sacred trees and groves, pollute healing wells and springs and build their own churches and cathedrals on ancient power spots where people had communed with spirits and deities since Neolithic times. Even today many churches and Christian sites, such as Lourdes, Fatima and Chartres, are build on sites that were sacred to the Goddess and the old Gods throughout history. They will probably continue to be places of power and inspiration long after the Christian churches disappear.

Where people continued to worship and live in the old ways sacred to the Goddess, church leaders whipped up fears and fantasies about their arch nemesis, Satan. They did this by twisting and distorting the time-honoured archetypal images of divinity, namely that of the Great Cosmic Mother and her other Self and consort, the Horned God.

As Christianity and the old nature religions clashed in Europe, missionaries used the image of the Divine Son, the Horned God, as a representation of the Christian Satan. In time any horned figure called up images of Satanic mischief. Ironically, wearing horns as a symbol of honour and respect was a widespread custom, originating in Neolithic hunting cultures. The horned head-dress eventually became stylized as the royal crown. This was a logical development since a repeatedly successful hunter assumed an increasingly prominent and respected role in the tribe, which evolved into that of the chieftain or king. William G Gray, a scholar of Western spiritual traditions, has pointed out that the Stone Age tradition of the hunter who laid down his life for the tribe was extended to that of the king who laid down his life for the people. 'The hunter-son must die' became 'the king must die'.

But wearing horns was a widespread custom not confined to Neolithic hunting societies. The ancient Greek Gods Pan and Dionysus were depicted wearing horns, as was Diana, the huntress, and the Egyptian Isis. Alexander the Great and Moses, neither actually Gods, were honoured among their followers with horns as a sign of their prowess and the divine favour that seemed to bless their exploits. Horns were a physical representation of the light of wisdom and divine knowledge that radiates from them (much like halos). Deuteronomy tells us that Moses' 'glory if like the firstling of his bullock, and his horns like the horns of the unicorn'. Horns were also used on Greek, Roman and Italian war helmets up to the fourteenth century as a symbol of strength and valour. And as William G Gray and Dr Leo Martello have each pointed out, Jesus, with his crown of thorns, has become another image of the great Western archetype of the king who laid down his life for his people.

Many customs and terms continue to reflect the importance that horns once held in local folklore. The word scorn comes from the Italian word that means 'without horns', for to be without horns was a sign of disgrace, shame or contempt. Holding up the index and little fingers in the form of horns was a gesture to ward off the evil eye. Today it means 'bull'. The lucky horseshoe is shaped like curved horns. And since it was the male animal that had horns, the horn easily became a phallic symbol. Leo Martello has called our attention to the fact that the contemporary adjective 'horny', which up until recently applied only to men, is also derived from these concepts.

Among the old European nature religions the male deities (the goat-footed, Greek nature God Pan, the Roman Faunus, the Celtic Cernunnos) represented the Son of the Great Cosmic Mother. Together Mother and Son embodied the powerful, lusty, life forces of the earth. The priestesses of the Old Religion honoured the Goddess and her Horned Consort by adorning their priests with horns and wearing the crescent, horn-shaped moon on their own foreheads. Against these old religious practices the church waged a bitter campaign. Among their weapons were the teachings that woman was evil. Witchcraft was the work of the devil and the horned representations of the God and Goddess were images of Satan. Underlying these attacks were the fears of women, sex, nature and the human body. Official church doctrine, worked out over the centuries by an all-male, celibate clergy, preached that woman was the source of all evil (since Eve trafficked with the serpent), and the earth was cursed by God (as a punishment for that sin), and that sex and the body were dirty and vile. 'The world, the flesh, and the devil' is the way it was - and is still ' summed up.

The church never accepted the ancient belief that the earth was sacred, alive with Gods and divine spirits. It could not understand or tolerate a spirituality that celebrated the human body, or the bodies of animals for that matter. As Christians beat their breasts, accused themselves of sins of the flesh and moaned about the drudgery of living in 'a valley of tears', Goddess worshippers sang, danced, feasted and discovered, as the Charge of the Goddess puts it, that 'all acts of love and pleasure are my rituals'. Protestants deplored the joyous activities of earthy rituals, like singing, dancing, chanting and merrymaking, even more than Catholics. Protestants theology attributed many of these directly to the devil. In the Old Religion, however, these were sacraments.

During the Burning Times a Christian conspiracy, consisting of both ecclesiastical and civil authorities, sought systematically to eliminate the old festivals. Church directives instructed local clergy to substitute Christian holy days for the pagan festivals. Christmas was established to conflict with the winter solstice, Easter with the spring equinox, the feast of St John the Baptist with the summer solstice, All Satints' Eve with the Celtic New Year, Samhain. And so it went throughout the year whenever there was a local pagan festival.

The authorities also preached against the merrymaking that took place on these holy days, especially rituals that involved sexual rites. In many pre-Christian cultures making love was a sacramental re-enactment of the creation. A church that mistrusted sex and women found it difficult to accept the idea that women's sexuality could be sacred. A spirituality that celebrated 'acts of pleasure' because they were sacred to the Goddess was a considerable threat to celibate priests and friars who found it difficult to tolerate lusty thoughts even in themselves.

Whose interests did the Witch-hunts serve? asks Starhawk in her perceptive book on Witchcraft, Dreaming the Dark. Stated that way, our attention is drawn to other factions, apart from the Christian churches, that also had vested interests in eliminating Witches and anyone they chose to label a Witch. Who were these other interests that supported and engaged in the persecution?

For one, the growing commercial elements in late medieval societies were beginning to consider land as a commodity that could be bought, owned and sold. The tradition out-look, so sacred to the earth-centred cultures of our ancestors, had been that no one owned the land - not even the lords owned it in the sense that they could sell their land if they wanted. Land belonged to the community; even peasants had rights, such as collecting firewood in the forests and grazing their animals on the commons, and the right to live on the land. The lords of the realm were honour-bound to respect these rights. As a market economy developed, however, the so-called landowners began expropriating the land for themselves and driving out peasants who stood in the way.

The enclosure movement, which began in the high Middle Ages and continued down into the nineteenth century, severely disrupted peasant life. By 'enclosing' common lands to be run under their own jurisdiction, landowners deprived peasants of their age-old rights. The feudal concept of land as an organism shared by all elements of society was gradually eroded by a market economy. In the process entire villages were depopulated. Thousands of peasant families were driven further into the unsettled areas or lured into the towns and growing cities to work as wage earners for the new industries. Village pagan life was disrupted, neighbours began to fear neigbours, and, as often happens, scapegoats were needed to explain the unsettled times. How easy it was for the church and wealthy interests to exploit this situation by launching Witch-hunts in local areas against individuals who believed in the old ways and fought for a way of life based on the oneness of the land and the sacredness of the earth.

In addition to wealthy commercial interests and land-owners eager to exploit the land, the medical profession also took an interest in the persecution of Witches and those healers who offered an alternative to the medical practices taught in the universities of the day. The effort to establish a professional medical community involved restricting medical knowledge to those who took formal courses of study. They, of course, could then set their own fees and exclude anyone they did not deem fit to practice. It is not surprising that they deemed women unfit to be healers. As the Malleus malificarum stated, 'If a woman dare to cure without having studied, she is a Witch and must die.' It was as simple as that.

Witches had, of course, studied, but not in the universities. They studied in nature, learned from older women in the community, experimented on their own, asked advice from the plants and herbs themselves. What really galled the medical profession and the church was that Witches were good at healing. In 1322 a woman was arrested for practising medicine and tried by the medical faculty at the University of Paris. Although the verdict stated that she was 'wiser in the art of surgery and medicine than the greatest master or doctor in Paris', it did little to win the male medical profession's respect for women healers.

Many Witch remedies were painless and more effective than the bleeding, leeching and purging that were standard medical practices until the twentieth century. And for many people a Witch's charms and spells were the only available medicine. Witches were also scapegoats for ignorant physicians. When a doctor couldn't cure someone he could always blame it on a Witch. Ironically, miraculous cures, when performed by a doctor, were attributed to God or the intervention of saints. Witches' miraculous cures were the work of the devil!

A Witch's healing skills were also subversive of religious orthodoxy. Eliminating pain was un-Christian. Because of Adam and Eve's fall, people were supposed to suffer, especially in childbirth, for the God of the Old Testament had cursed woman and told her that she would have to bear children in pain and in sorrow. Kraemer and Sprenger claimed that 'no one does more harm to the Catholic faith than midwives'. What they had in mind was both the painless births that defied the patriarchal God's curse on woman and the fact that Witches did not baptize the newborn. Witches had painkillers, anti-inflammatory treatments, digestive aids, contraceptive drugs and many other herbal and natural treatments that today are the bases of many pharmaceutical products. Their knowledge of how to ease childbirth and hasten recovery made them the best midwives. No wonder the medical profession launched a campaign to eliminate midwifery as a legitimate calling!

Women were denied professional status as healers by an all-male, medical-religious establishment eager to discredit natural healing techniques as being superstitious, ineffective and even dangerous. We now know from anthropological studies of people in Africa, Polynesia and North and South America that one of the most effective ways to destroy a culture is to destroy confidence in its healers and spiritual leaders. When these two roles are undermined, people become demoralized, their way of life collapses and they are more easily assimilated into the value system of the invading forces, be they political or ecclesiastical. The rising professions, in league with church authorities, did precisely that all across Europe. They created the image of a Witch as a meddlesome, superstitious huckster of ineffectual and dangerous cures and remedies. And they said her Horned God was the Christian Satan.

To justify the millions of executions, the church created a systematic demonology around pre-Christian folk beliefs, practices and holidays. To these were added the fantasies about pacts with the devil, bizarre and sadistic sexual rites and obscene travesties of Catholic ceremonies. The worst Christian fears about salvation and eternal punishment were projected on to innocent people who were accused of being in league with the devil. The sexual nature of the hysteria over Witches seems a logical result of the sexual repression based on religious doctrine. In a sense the Witch-hunts were more about sex than about devil worship. Of course, when the 'accused' women were asked if they dreamed of the devil, many said they did. The devil was a major theme in medieval and Renaissance culture. The devil was talked about, feared, depicted and blamed for all that went wrong. It is normal for people to dream about the cultural images that make up so much of their lives. I am sure Witch-hunters also dreamed about the devil, and they probably also dreamed about Witches dreaming about the devil!

Armed with the Malleus malificarum, Witch-hunters entered villages and hamlets and began their search. The official guidebook suggested that children made the best informers because they were easily intimidated. A routine custom was to give teenage girls two hundred lashes on their bare backs to encourage them to accuse their mothers or grandmothers of Witchcraft. So-called evidence of Witchcraft was varied, illogical and unevenly applied. For example, if on being accused, a woman muttered, looked down to the ground or did not shed tears, she was a Witch. If she remained silent, she was a Witch. Dissimilar eyes and pale blue eyes were thought to indicate a Witch, as did the 'devil's mark' (often a smaller, third nipple, which about one out of three women has). A wart, mole or birthmark also qualified as a mark of the devil, as could freckles.

If the 'devil's mark' could not be found, an inquisitor intent on establishing a given woman as a Witch could assume that the mark was cleverly concealed so that it would go undetected. A formal search of the woman's entire body was then conducted, usually in public before curious on-lookers who were often more interested in seeing the woman nude than in finding the mark of the devil. Searching a woman's body for signs of the devil led to such widespread cases of rape that bishops eventually wrote directives to discourage the 'zeal' with which inquisitors pursued their quarry.

The search might be conducted with a 'Witch pricker', an instrument resembling an ice pick. Professional Witch-hunters (who were paid only when they could convince the local authorities that they had captured a Witch) often used two prickers, a normal one and another with a retractable point that slid up into the handle. After drawing blood on various parts of the body with a regular pricker to establish its sharpness, the Witch-hunter could then secretly switch prickers and 'plunge' the blade of the retractable pricker up to the hilt into the body of the accused woman. Feeling no pain was evidence of a Witch.

The principle of 'corpus delecti' was not necessary to establish the 'crime' of Witchcraft. One did not need an actual victim or evidence of a bona fide crime. Hearsay, accusations and bogus testimony of others in the community were sufficient. In Salem Village a common sign of Witchcraft was 'mischief after anger'. In other words, if two women quarrelled and the children of one of them became sick or her cow died, she could assume that this 'mischief' was the work of the woman with whom she had quarrelled. The mischief was 'magic'; the woman was a 'Witch'. Inability to recite the Lord's Prayer in public before an investigating committee without stumbling over the words was also considered a sign of Witchcraft.

According to Barbara Walker's Woman's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets, a woman who lived alone was considered a Witch, especially if she resisted courtship. In England a woman was murdered by a group of soldiers who saw her surfing on a river. ' .... She fleeted on the board standing firm bolt upright,' they reported, and so they assumed she was practising magic. When she came onshore they shaved her head, beat her and shot her to death. One woman playfully ran down a hill in front of an empty bucket, calling it to follow her. Those who saw her little game thought it was sorcery. She was brought before the authorities for Witchcraft. A Scottish Witch was arrested for bathing neighbourhood children, a practice in hygiene that was frowned upon in that day.

There were rules about torture, as if that somehow made it more humane. For example, torture was never to last more than one hour. But inquisitors could stop a session just short of an hour and so begin again. There were three approved bouts: one to elicit a confession, a second to determine the motive and a third to incriminate accomplices and sympathizers. Sometimes torture went around the clock. Ankles were broken, breasts cut off, eyes gouged out, sulphur poured into hair on the head and other parts of the body and set on fire, limbed pulled out of sockets, sinews twisted from joints, shoulder blades dislocated, red-hot needles thrust beneath fingernails and toenails and thumbs crushed in thumbscrews. Victims were given scalding baths in water mixed with lime, hoisted on ropes and then dropped, suspended by their thumbs with weights attached to their ankles, hung head-down and revolved, singed with torches, raped with sharp instruments, pressed beneath heavy stones. Sometimes family members were forced to watch another tortured before their own ordeal. On the way to the stake victims might have their tongues cut out and their mouths scoured with a red-hot poker to prevent them from blashpeming or shouting obscenities during the execution. The inquisitor Nicholas Remy was astonished that, as he noted, so many Witches had 'a positive desire for death'. It is hard to believe that he could not understand why.

|

|||

|

|